Sharks, Bora Bora, & Engaging M&A Markets II: Types of "Sharks" (Buyers)

As discussed in my last post, the process of taking a company to market for investment or M&A can be a lot like my experience swimming with sharks. While it should be safe, that does not mean it won’t be uncomfortable or that preparation / precaution is not important. At the end of the last post, I introduce a few concepts that I’ll cover in some detail today and in further detail in future posts.

In many cases, the best ultimate partner (strong strategic, cultural, and economic [valuation] fit) for a business did not present itself before the process (i.e. you had to proactively find them under the surface). This raises the question: how does one identify the right buyer? In introducing a framework to answer that question, I’ll also introduce a few nuances and comment on why entrepreneurs should always endeavor to understand what the entire market has to say before closing a transaction (i.e. “run a process”). A related question is “why can’t I wait for the single best partner to find me?” In the commentary below, I’ll introduce and answer this question as well as whether the buyer version of “Jaws” exists, how to protect yourself, and other factors related to “the dive” / M&A process.

How to identify the best bidders / most likely to clear the market

During my shark dive in Bora Bora, I saw mostly 4-6 ft. reef sharks. With dozens in the water, they were all around me, looked and behaved similarly to each other, and had no distinguishing characteristics that immediately jumped out. That was until my guide got involved. After I had calmed down and become comfortable following 5 minutes or so of swimming (felt more like 30 minutes), my guide joined and pointed out sharks that had clearly been in fights based on their scarring, one that had a hook in its mouth, the distinguishing characteristics of males vs. females, likely age of the sharks based on size, and other distinguishing characteristics. He also pointed out two very different sharks circling well below the others. With the robust group of reef sharks circling close by, I had missed two much larger, ~10 foot lemon sharks 30 feet below us in the water. As my guide pointed out, it was important that we continue to keep an eye on the lemon sharks because, while they are much harder to get interested (i.e. to come to the surface), they are much more aggressive when their interest is piqued. Bora Bora has experienced very few shark-on-human accidents, but in the few cases where an injury has occurred, lemon sharks have generally been the culprit. My guide also explained how enjoyable they are to swim with in the right setting (locals often ride on them by holding their dorsal fins), that they are often 10x larger by weight than reef sharks (the two below us were probably 200 lbs each vs. 20-25 lb reef sharks), that most bites from a lemon shark are due to them being spooked, and that (despite their much larger size) there have been no known human fatalities due to a lemon shark bite.

As the foregoing shows, a shark is not a shark like all other sharks. Each has distinguishing characteristics and often the larger, more impressive sharks are harder to find and harder to attract. This illustration leads nicely to the previously posed question: “why can’t I wait for the best buyer to find me?” The high-level answer is that the best buyer might never find you and if it does, it is not clear you will be prepared to swim with it. To continue the analogy, I have compared categories of buyers / investors to sharks. The list below is not exhaustive and includes introductory content that I’ll get into much deeper in future posts, but it does begin to paint the picture:

- The domesticated shark: this class of buyer may be a perfect partner (ability to pay and add value, fit, etc). However, based on its size and status, it has become accustomed to investment bankers, investors, and other relationships bringing transactions to it, particularly if the transaction is not especially large. This is true of many large strategic buyers that do not need to proactively seek good opportunities in order to be “fed”.

- The foot soldier shark: this is a “gate-keeper” shark that answers to an alpha and is less likely to be thoughtful about strategic, cultural, and economic fit. Generally the individual who fits this role is quite career-oriented and is looking to introduce deals to the alpha that are less risky and offer career path upside. Therefore, due to a lack of experience / creativity, they will miss some very good deals that the alpha would almost certainly be interested in. The foot soldier shark is common in many private equity funds and with large strategic buyers where more junior professionals work to uncover opportunities that their senior team members will like but also miss ones where the inputs (revenue, growth, profit, etc) don’t obviously check all the boxes in their opportunity-scoring rubric.

- The distracted shark: this can be true of any good potential buyer at any time. Pure and simple, sometimes great potential partners (PE and strategic) are busy with other things so they miss a perfect “meal.” Perhaps they are working on a large, complicated deal that is taking up all of their resources; perhaps the senior professional who is the perfect advocate for the deal just welcomed a new child or had a death in the family. Because distractions are real for everyone at some point, it is important to be proactive in a process to ensure that a great fit doesn’t fall flat due to a lack of exploration.

- The lazy shark: the “lazy” shark could also be called the “resting” shark or the “pragmatic” shark. These potential partners for one reason or another (perhaps their fund has been fully deployed, they just closed a large “needle moving” deal, or they are slowing down on M&A for other reasons) have decided not to be proactive about M&A for a season. However, they still might do a great deal that is brought to them.

- Sharks that almost exclusively rely on bounty hunters for food: for some private equity firms as well as strategic buyers, they have strategically made the decision to be less outbound (directly to target companies) in their deal sourcing. While they recognize the importance of being in front of the right companies, they have decided to spend their time differentiating themselves, communicating what they are interested in, and building a deal pipeline through investment bankers. Therefore, rather than reaching out directly to companies, they come to people like me to ensure they see every “banked” deal that fits their interests. They then tend to pay a premium price when such deals arrive. Groups like this can be perfect fits, as they know exactly what they are looking for and are always prepared to do a deal when they see it. However to “see it,” the deal must be brought to them, so it is a subset of buyer that is exclusive to M&A processes run by advisors.

- The formerly vegetarian shark: there is a first deal for every buyer; and some great buyers have never yet done a deal. For these sharks it is important that they work with firms that know how to communicate value, walk them through what it will take to win, and help them justify the deal price to themselves, their investors, and other stakeholders. With such buyers, their first deals are often banker-led deals because it is so important to leadership that the first deal becomes a successful deal.

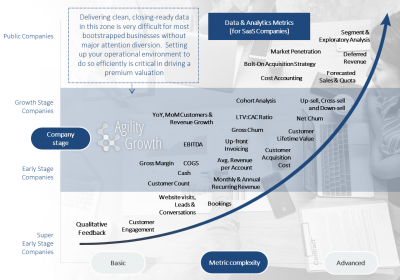

As is introduced above, buyers come in many shapes and sizes and there are a multitude of reasons why a great potential partner might not be in a position to proactively find your business, even if there is a great fit. The makeup of buyers is different, so the “chum” covered in my previous post might need to be different to attract the acquirer / investor’s attention. For some firms like the outbound firms calling your company on a regular basis, it may seem like you could partner without a proactive process; and for other firms, you might never know how great the fit is without an introduction from a third party. And for all potential partners, like the shark, they ultimately are governed by their nature in how they do deals. Great buyers still don’t want to pay a premium multiple (expend calories to hunt) if they don’t have to because their returns are higher if the price is lower. Therefore, they tend to only pay their best price in an environment where all signals credibly convey that there is competition for the “meal” / your transaction. With strategic buyers, sometimes they are in the business of doing deals, have a corporate development function, and are unlikely to miss on a great fit. In other cases, this is not true. With private equity firms, the differences can be more subtle; the best ones are willing to compete though they only want to win competitive processes if they are “true believers” and believe they are winning based on their value-adding capabilities and merits vs. getting a “cheap deal” as a result of an inefficient market.

Finally, in many deals an individual actor on the other side of a deal might be set for a big promotion if he has one final big win; others may be on thin ice due to a recent loss. All of these factors matter a lot in building a “feeding frenzy” for your company across buyers. This is why we always recommend running a deliberate process to identify the “right” partner. This theme is something I’ll discuss in tremendous detail across many posts, but for my next post, I'll answer the question "does 'Jaws' (i.e. an always scary, value destroyer) exist in an M&A context"?