The Working Capital Adjustment, Part III

This week we wrap our net working capital (NWC) series with a discussion of a common pitfall that sellers should guard against when negotiating a working capital adjustment. A deferred revenue liability, if improperly considered in NWC adjustment negotiations, can be used to dip into a seller’s pocket post-closing.

In Parts I and II of the series, we defined net working capital and identified the fundamental reason that it is important (Part I). We also introduced the philosophical rationale for including working capital adjustment language in definitive deal documentation (Part II).

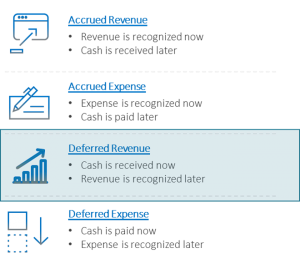

Because many sophisticated buyers frame the working capital adjustment in terms of self-preservation (see Part II), it is not uncommon for even financially refined sellers to look past an important category of current liability that is sometimes used to mine value from sellers at close. Deferred revenue’s impact on the NWC adjustment can be significant because it is not necessarily a ‘cash equivalent’ liability. This is because deferred revenue is carried on the balance sheet at the gross revenue level while the cost of delivering that revenue is usually much lower.

To illustrate, if a seller with 90% gross margins (not uncommon in SaaS and brand-differentiated communities) collects $1 million as deferred revenue, it should only cost the buyer $100,000 to deliver the revenue. Thus, $900,000 of the carried liability becomes marginal profit to the buyer if the entire $1 million is included as a reduction to net working capital. This will be the case if deferred revenue is not carved out of the calculation in some way. Given that many of our clients are high growth businesses, it is not unusual that 10-25% or more of the current year’s cash inflows would fall into the deferred revenue category if measured on a GAAP basis. This is particularly true in software models with high upfront customization / setup fees or where subscription fees are collected in advance. Such a percentage would most certainly move the needle in any transaction.

The GAAP vs. cash distinction raises another potentially huge, though somewhat easy-to-miss, issue as it pertains to deferred revenue’s impact on the net working capital adjustment calculation. Many bootstrapped companies recognize revenue on a cash basis, which means that the projections used to value the deal are also typically presented on a cash basis. In such cases, deferred revenue won’t show up on the balance sheet. This is because the receipt of cash triggers a revenue transaction on the income statement. However, buyers will often call for a NWC adjustment based on generally accepted accounting principles. This can be a huge problem if not caught. In fact, a seller might think that he is in a great working capital position when analyzing the company’s financial statements. However, a GAAP reclassification might trigger the creation of a deferred revenue account. If this happens, purchase price will be adjusted negatively. In the right (wrong) business, this accounting shift could cost millions. Be careful out there!